«ANOTHER FRIDA …»

Three women bring alive Frida Kahlo

Three women, the mezzo-soprano Katerina Roussou, the pianist Alexandra Nomidou and the actress Magda Mavroyanni, bring alive Frida Kahlo in the musical performance ”Another Frida …” on 10/8. They will approach her through the eyes of her sister and the texts written by herself in her diary, presenting the legend of Frida through a musical journey to Latin America and Mexico.

Alexandra Nomidou, piano

Magda Mavroyanni, narration

«I was painting a door over the dull windows and from this door, with my imagination, I was running away with great joy and fury …». With her art, the painter Frida Kahlo managed to turn into strength and motivation all the laminated blows of fate. «I hope the end is joyful – and I hope never to come back» Frida Kahlo wrote in her diary few hours before leaving her last breath in the famous Blue House. Yet, as if she never left, she comes back again and again since, with her works and her strong personality, she has left her stamp indelibly in the history of modern art.

This Frida, but through the eyes of her sister, of «one other Frida», will be presented by the mezzo-soprano Katerina Roussou, the pianist Alexandra Nomidou and the actress Magda Mavroyanni, on August 10th in the Concert Hall of Megaro Gyzi. They will reach her, by revealing the parallel, intense and complex life of the two women, through texts written by Frida herself in her diary or others for her, and with a lot of music from Latin America and Mexico (A. Piazzolla, A. Ginastera, H. Villa-Lobos, M. Ponce, C. Guastavino, E. Lecuona, E. Granados), but also works of F. Chopin, F. Poulenc, D. Shostakovitch and A. Scriabin. The program also includes a work by composer Stathis Gyftakis, based on a poem by Pablo Neruda.

KATERINA ROUSSOU, mezzo-soprano

Katerina Roussou studied singing at the Athens Conservatory of Music and Drama and received her Diploma in Singing with the Highest Distinction. At the same time she graduated from the National Technical University of Athens in the Department of Electrical Engineering. She received the “Maria Callas Scholarship” from the Athens Conert Hall “Megaron” and an award from the “Propondis Foundation” to continue her studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London (RAM) in the Postgraduate Course. In September 2007 she continued on the Royal Academy Opera Course (RAO), with the support of the “A. Onassis Foundation”, from which she graduated with the highest award in performance, DipRAM. She is currently studying on the postgraduate course at the Academy of Music of Ljubljana with Professor Alenka Dernač-Bunta.

Her operatic experience include the roles of Cherubino and Marcellina in Mozart’s “Le nozze di Figaro”, Vava in Shoshtakovich’s “Cheryomushki”, Il Destino and Furia II in Cavalli’s “La Calisto”, as well as Third Lady for British Youth Opera’s production of “The Magic Flute”. She has performed one of the Flowermaidens in Wagner’s “Parsifal” for the London Wagner Society.

As a soloist she has sung with the Athens State Orchestra (Mozart arias), the Symphonic Orchestra of the Greek Television (arias and duets, Mozart “Requiem”), the Ljubljana Philharmonic Orchestra (arias), the International Bachakademie under Helmut Rilling in Greece and Germany (Bach cantatas), the Orchestra and Choir of the “Filippos Nakas Conservatory”, the Orchestra and Choir of High Wycombe. In April 2010 she sang in a gala benefit concert at the Athens Megaron with world famous tenor Jose Cura. At the Athens Megaron she has also sung in opera scenes and in a gala concert for the Maria Callas Scholarship holders. At the Palacio de Festivales in Santander-Spain she sang “5 poemas de Javier Alfaya” by David del Puerto (Sala Argenta) and in a gala concert (Sala Pereda).

As part of the celebration of the Academy of Music of Ljubljana’s jubilaeum, she sang the Alt-solo in Mahler’s “2nd Symphony” with the Symphonic Orchestra of the Academy under Anton Nanut in Trieste (Sala Tripcovich) and Ljubljana (Cankarjev Dom-Gallusova Dvorana). In November 2009 she sang in a concert in the honour of the President of the Hellenic Democracy on the occasion of his official visit to Slovenia. She participated in the festival “Encuentro de Musica y Academia” in Santander, where she had masterclasses with Teresa Berganza and a series of solo recitals. She has worked closely with the famous pianist Elizabeth Cooper: as a guest in the summer festival “Plaisir de musiques” that she organizes in Annecy, as well as in the annual concert of the Gouverneur Militaire in Paris in the cathedral St Louis des Invalides.

She has given a number of recitals in Greece (“Parnassos” Recital Hall, Psichiko Cultural Centre, Megaro Gyzi Cultural Centre, Symi Festival, Bellonio Center, P. N. Nomikos Congressal Center) and abroad (Spain, UK, Slovenia, France). She has also sung in many oratorios: A. Vivaldi “Beatus vir”, G.B. Pergolesi “Stabat Mater”, C. Saint-Saëns “Oratorio de Noël”, J.S. Bach “Weihnachtsoratorio”, “Matthauspassion”, J. Haydn “Schopfungsmesse”, W.A.Mozart “Missa brevis in d”, L.v.Beethoven “Messe in C”.

She won first prize at the “Isabel Jay Memorial Prize for Opera” and was Highly Commended at the National Mozart Competition (London 2007). She has recorded excerpts from Mozart’s “Le nozze di Figaro” (Marcellina) for BBC Radio3, 5 songs by Markos Dragoumis for the literary magazine “Nea Synteleia” and 2 songs on poems by Giorgos Karter for the State Radio of Thessaloniki.

The pianist Alexandra Nomidou graduated from the Athens Conservatory and continued her studies in Paris. She has appeared many times in the Athens “Megaron” Music Concert Hall and in many known concert halls in France, England, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Turkey, Brazil and USA, as a soloist with major orchestras and in chamber music concerts, mainly with “Trio Hellenique”. She has recorded two albums with EMI, with works by Schumann, Schubert, Brahms and Ravel, which received excellent reviews. Since 2005, Alexandra Nomidou has created in Athens the cycle of concerts «Around the piano”, which she runs as artistic director. She lives and works in Paris.

Magda Mavroyanni, actress – director – musician – author

Magda Mavroyanni is inspired by women personalities from the arts who left their indelible mark in time, such as Clara Schumann, Anna Magdalena Bach, Coco Chanel, Princess Sissy, Frida Kahlo and others. The actress, director, musician and author Magda Mavroyanni has studied music and theater in Athens and Paris, where she began her career. She has professional experience as actress and director, while she specializes mainly in musical lecterns that combine the speech with the music.

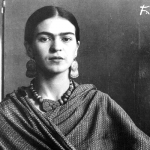

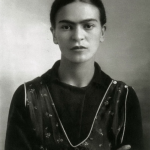

Frida Kahlo (1907- 1954)

(full name: Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón)

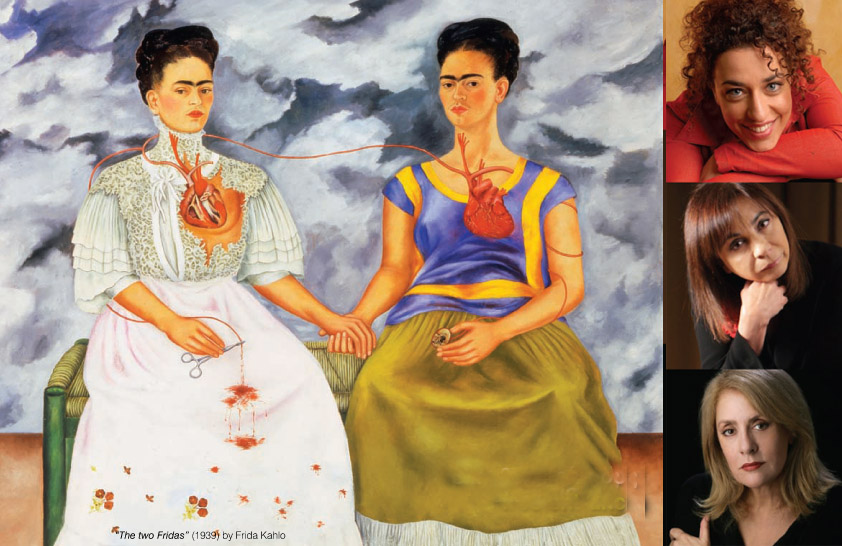

«In 1953, when Frida Kahlo had her first solo exhibition in Mexico (the only one held in her native country during her lifetime), a local critic wrote: ‘It is impossible to separate the life and work of this extraordinary person. Her paintings are her biography.’ This observation serves to explain both why her work is so different from that of her contemporaries, the Mexican Muralists, and why she has since become a feminist icon.

«Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907, the third daughter of Guillermo and Matilda Kahlo. Her father was a photographer of Hungarian Jewish descent, who had been born in Germany; her mother was Spanish and Native American. Her life was to be a long series of physical traumas, and the first of these came early. At the age of six she was stricken with polio, which left her with a limp. In childhood, she was nevertheless a fearless tomboy, and this made Frida her father’s favourite. He had advanced ideas about her education, and in 1922 she entered the Preparatoria (National Preparatory School), the most prestigious educational institution in Mexico, which had only just begun to admit girls. She was one of only thirty-five girls out of two thousand students.

«It was there that she met her husband-to-be, Diego Rivera, who had recently returned home from France, and who had been commissioned to paint a mural there. Kahlo was attracted to him, and not knowing quite how to deal with the emotions she felt, expressed them by teasing him, playing practical jokes, and by trying to excite the jealousy of the painter’s wife, Lupe Marin.

«In 1925, Kahlo suffered the serious accident which was to set the pattern for much of the rest of her life. She was travelling in a bus which collided with a tramcar, and suffered serious injuries to her right leg and pelvis. The accident made it impossible for her to have children, though it was to be many years before she accepted this. It also meant that she faced a life-long battle against pain. In 1926, during her convalescence, she painted her first self-portrait, the beginning of a long series in which she charted the events of her life and her emotional reactions to them.

«She met Rivera again in 1928, through her friendship with the photographer and revolutionary Tina Modotti. Rivera’s marriage had just disintegrated, and the two found that they had much in common, not least from a political point of view, since both were now communist militants. They married in August 1929. Kahlo was later to say: ‘I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down… The other accident is Diego.’

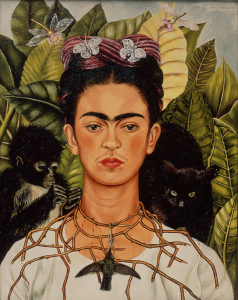

«The political climate in Mexico was deteriorating for those with left-wing sympathies, thanks to the reactionary Calles government, and the mural-painting programme initiated by the great Minister of Education Jose Vasconcelos had ground to a halt. But Rivera’s artistic reputation was expanding rapidly in the United States. In 1930, the couple left for San Francisco; then, after a brief return to Mexico, they went to New York in 1931 for the Rivera retrospective organized by the Museum of Modern Art. Kahlo, at this stage, was regarded chiefly as a charming appendage to a famous husband, but the situation was soon to change. In 1932 Rivera was commissioned to paint a major series of murals for the Detroit Museum, and here Kahlo suffered a miscarriage. While recovering, she painted Miscarriage in Detroit, the first of her truly penetrating self-portraits. The style she evolved was entirely unlike that of her husband, being based on Mexican folk art and in particular on the small votive pictures known as retablos, which the pious dedicated in Mexican churches. Rivera’s reaction to his wife’s work was, however, both perceptive and generous.

Frida began work on a series of masterpieces which had no precedent in the history of art – paintings which exalted the feminine quality of truth, reality, cruelty and suffering. Never before had a woman put such agonized poetry on canvas as Frida did at this time in Detroit. Kahlo, however, pretended not to consider her work important. As her biographer Hayden Herrera notes, ‘she preferred to be seen as a beguiling personality rather than as a painter.’ From Detroit they went once again to New York, where Rivera had been commissioned to paint a mural in the Rockefeller Center. The commission erupted into an enormous scandal, when the patron ordered the half-completed work destroyed because of the political imagery Rivera insisted on including. But Rivera lingered in the United States, which he loved and Kahlo now loathed. When they finally returned to Mexico in 1935, Rivera embarked on an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina. Though they finally made up their quarrel, this incident marked a turning point in their relationship. Rivera had never been faithful to any woman; Kahlo now embarked on a series of affairs with both men and women which were to continue for the rest of her life. Rivera tolerated her lesbian relationships better than he did the heterosexual ones, which made him violently jealous.

One of Kahlo’s more serious early love affairs was with the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky, now being hounded by his triumphant rival Stalin, and who had been offered refuge in Mexico in 1937 on Rivera’s initiative. Another visitor to Mexico at this time, one who would gladly have had a love affair with Kahlo but for the fact that she was not attracted to him, was the leading figure of the Surrealist Group, André Breton. Breton arrived in 1938 and was enchanted with Mexico, which he found to be a ‘naturally surrealist’ country, and with Kahlo’s painting. Partly through his initiative, she was offered a show at the fashionable Julian Levy Gallery in New York later in 1938, and Breton himself wrote a rhetorical catalogue preface. The show was a triumph, and about half the paintings were sold. In 1939, Breton suggested a show in Paris, and offered to arrange it. Kahlo, who spoke no French, arrived in France to find that Breton had not even bothered to get her work out of customs.

«The enterprise was finally rescued by Marcel Duchamp, and the show opened about six weeks late. It was not a financial success, but the reviews were good, and the Louvre bought a picture for the Jeu de Paume. Kahlo also won praise from Kandinsky and Picasso. She had, however, conceived a violent dislike for what she called ‘this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches of surrealists.’ She did not renounce Surrealism immediately. in January 1940, for example, she was a participant (with Rivera) in the International Exhibition of Surrealism held in Mexico City. Later, she was to be vehement in her denials that she had ever been a true Surrealist. ‘They thought I was a Surrealist,’ she said, ‘but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.’

«Early in 1940, for motives which are still somewhat mysterious, Kahlo and Rivera divorced, though they continued to make public appearances together. In May, after the first attempt on Trotsky’s life, led by the painter Siqueiros, Rivera thought it prudent to leave for San Francisco. After the second, and successful attempt, Kahlo, who had been a friend of Trotsky’s assassin, was questioned by the police. She decided to leave Mexico for a while, and in September she joined her ex-husband. Less than two months later, while they were still in the United States, they remarried. One reason seems to have been Rivera’s recognition that Kahlo’s health would inexorably deteriorate, and that she needed someone to look after her.

«Her health, never at any time robust, grew visibly worse from about 1944 onwards, and Kahlo underwent the first many operations on her spine and her crippled foot. Authorities on her life and work have questioned whether all these operations were really necessary, or whether they were in fact a way of holding Rivera’s attention in the face of his numerous affairs with other women. In Kahlo’s case, her physical and psychological sufferings were always linked. in early 1950, her physical state reached a crisis, and she had to go into hospital in Mexico City, where she remained for a year.

«During the period after her remarriage, her artistic reputation continued to grow, though at first more rapidly in the United States than in Mexico itself. she was included in prestigious group shows in the Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Institute of Contemporary Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1946, however, she received a Mexican government fellowship, and in the same year an official prize on the occasion of the Annual National Exhibition. She also took up teaching at the new experimental art school ‘La Esmeralda’, and, despite her unconventional methods, proved an inspiration to her students. After her return home from hospital, Kahlo became an increasingly fervent and impassioned Communist. Rivera had been expelled from the Party, which was reluctant to receive him back, both because of his links with the Mexican government of the day, and because of his association with Trotsky. Kahlo boasted: ‘I was a member of the Party before I met Diego and I think I am a better Communist than he is or ever will be.’

«While the 1940s had seen her produce some of her finest work, her paintings now became more clumsy and chaotic, thanks to the joint effects of pain, drugs and drink. Despite this, in 1953 she was offered her first solo show in Mexico itself – which was to be the only such show held in her own lifetime. It took place at the fashionable Galeria de Arte Contemporaneo in the Zona Rosa of Mexico City. At first it seemed that Kahlo would be too ill to attend, but she sent her richly decorated fourposter bed ahead of her, arrived by ambulance, and was carried into the gallery on a stretcher. The private view was a triumphal occasion.

«In the same year, Kahlo, threatened by gangrene, had her right leg amputated below the knee. It was a tremendous blow to someone who had invested so much in the elaboration of her own self image. She learned to walk again with an artificial limb, and even (briefly and with the help of pain-killing drugs) danced at celebrations with friends. But the end was close. In July 1954, she made her last public appearance, when she participated in a Communist demonstration against the overthrow of the left-wing Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. Soon afterwards, about a week after her forty-seventh birthday, Kahlo died on July 13 at her beloved Blue House. She died in her sleep, apparently as the result of an embolism, though there was a suspicion among those close to her that she had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read: «I hope the end is joyful – and I hope never to come back – Frida».

Since her death, Kahlo’s fame as an artist has only grown. Her beloved Blue House was opened as a museum in 1958. The feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity. In 1983, Hayden Herrera’s book on the artist, A Biography of Frida Kahlo, also helped to stir up interest this great artist. More recently, her life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida, starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Diego Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

[ Text from Edward Lucie-Smith, «Lives of the Great 20th-Century Artists» ]